Well, this is a long overdue installment for this column and there is a lot of catching up to do. First, I’d better remind people about the rules and conditions under which this column operates. To sum up:

- I review only short fiction by Australian authors (howsoever described)

- and I review only those stories I am inclined to review, which does not necessarily mean I like each story included, but that I think each story possesses some quality that recommends it.

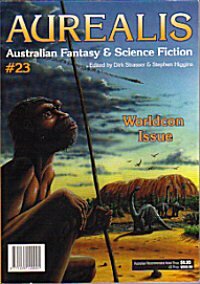

This time around, we’ve got stories from Orb #0, Aurealis #23, Altair #4 and Eidolon #28.

I promise to write another column soon, covering most of the Australian shorts printed since the WorldCon last year.

The first issue of Sarah Endacott and Anthony Oakman’s Orb (more accurately, issue #0) has several fine stories, and bodes well for the magazine’s future.

Sue Isle’s "Sisterchild" is about Simeon and Leah, Siamese twins born into a post-apocalyptic Australian tribe. Leah is nothing more than a torso and head sprouting from Simeon’s waist, and their tribe decides Leah has to be cut out so that her brother can enter manhood as a properly formed male. Although this is a death sentence for his sister, Simeon is tempted at first, but at Leah’s urgings and overwhelmed by guilt, he flees into the desert. Picked up by a trio of men who wander the desert in a Sherman tank (I kid you not), who are shocked but not offended by Leah, they are taken to a town where the technology exists that can safely separate them.

Ultimately, this fine little tale is not about whether or not the twins gain independence from each other, but about what effects the promise of this independence has on Simeon, who believes he has always wanted to lead a "normal" life.

In the end, "Sisterchild" reads like it should belong to something bigger – a novella or novel, perhaps. The background and the characters deserve more room. For all that, Simeon and Leah are sympathetic characters, drawn without sentimentality.

In Terry Dowling’s "Down Flowers", Tom Rynocceros must try and solve the mysterious death of an Ab’O Martian colonist, Bellin Say Jana, who returned to Earth for reasons of tribal honour. There is more at stake here than simply an unexplained fatality, and Downing uses his gift of language to tease us with the possibility of a multitude of red herrings. Too late, we realise there are no such things as red herrings in Dowling’s future Australia; every clue is another piece in the giant jigsaw of that future he has been putting together now for over fifteen years.

That Tom will solve the mystery of the Martian’s death is never an issue, but the joy of reading the story is the discovery that his death is not the real mystery at all.

Ultimately, however, I was dissatisfied with "Down Flowers". Its hints at life in the bizarre and dangerous Martian colony promises new cornucopia of Dowling exotica and imaginings, and to be confronted with a Tom Rynocceros story where Tom and his Australia are overshadowed by the promise of something even more extraordinary left me wondering if it wasn’t time for both Tom Rynocceros and Earth to be left behind for even stranger wanderings.

Adam Browne’s "Account Dracula" is about an obsession with prime numbers and cats; the fact that the owner of both obsessions is a vampire makes for a neat twist and provides the story with some delightfully perverse moments. Exactly how the vampire pursues her obsessions to their extreme and logical conclusion is something I’ll leave the reader to discover, but it is a wonderful conceit.

But, while clever and well written, the ending is telegraphed too soon and lets down the rest of the story. There should have been more.

Rick Kennett is a writer we’re lucky to have among us, but I can’t help feeling he would have found the success he deserves if he had been born a century and a half ago and was telling his tales to an audience which appreciates finesse over gore. "Isle of the Dancing Dead" is a clumsy title for a magical little ghost tale. The problem with stories such as this is that they should be read between their brothers, and not diluted among a grab bag of stories from other genres (however fine those other stories may be). I would love to see "Isle of the Dancing Dead" appear in a Kennett collection, a collection I think would give as much pleasure as those by M. R. James or Erckmann-Chatrian.

I did not enjoy reading Robert Hood’s "Primal Etiquette", a visceral tale that has about as many body parts as adjectives, but the fact that I read it from beginning to end is testimony to Hood’s skill as a writer. In fact, "Primal Etiquette" is a gruesome gag with quite a funny punch-line. Describing the story at all would likely give the punch-line away, so this is something you should read for yourself; just keep a barf bag handy.

Robert Hood makes another appearance in Aurealis #23, the magazine’s special WorldCon issue. "Ground Underfoot", despite the science fiction overalls, is really a ghost story. In a world shattered by the random and destructive visits of a giant monster, insurance companies are making a killing (literally). The companies rely on people sensitive to the appearance of the monster to calculate their rates, and penalise insurance cheats with execution. Danforth is a hitman for one of these companies, but unbeknown to his employers he is also a sensitive. Sent on a mission to recover the world’s leading authority on the monster, lost or kidnapped somewhere in Sydney, Danforth discovers there is something about his talent that even he was unaware of.

Helen Sargeant’s "Landlocked" is a sparsely elegant short story that arouses in the reader a great sympathy for its two protagonists, a young girl paralysed in an horrific accident that killed her father, and one of the nurses who looks after her. The young girl has the ability to know what is going on in other people’s lives, and increasingly uses the knowledge to lash out at those closest to her. While there is no surprise in the story’s ending, Sargeant handles it deftly, and the final horror is like an invisible finger gently, terribly, stroking the back of your neck.

In Trudi Canavan’s "Whispers of the Mist Children", Velarin Initha is a "sora" or witch travelling with a desert caravan and employed by the caravan’s leader to protect it from brigands. She must do this without harming any of the brigands, since doing so would be against the rules of her order. Velarin holds a terrible secret, her failure to protect her first employer, a king in constant danger of assassination. "Whispers" reads like a draft for a much longer work, and the protagonist deserves more room to stretch her legs. This is the first published story for someone better known in the genre as an artist; while slight, it is told with vigour and promises better to come.

Sean Williams’ "Evermore" in Altair #4 deals with beings who discover that a long life can mean nothing more than a pointless existence extended beyond endurance. The protagonist and his companions are engrams – electronic copies of biological humans – sent on a journey in a small probe to a distant star. An accident near their destination means they miss the star, and only the work of one of their number keeps the probe working as a viable environment for its sentient cargo.

The problem is that although the engrams are copies of people who were all brilliantly successful in their own particular field, they themselves cannot achieve anything great because the ability to compose great music or write great poetry, for example, depends on memory. Although the engrams possess the memories of their antecedents they have never actually experienced them. The problem is made worse because the engrams exist within a program with parameters that confines them to think and behave like the originals they are based on. There is no scope for the engrams to evolve identities in their own right, to develop new patterns of behaviour or to interpret their experiences since leaving Earth. And there is no way that the program’s parameters can be changed.

Or so they thought.

Robert Stephenson makes an appearance in his own magazine with "Breaking the Ice". Carmen is a reluctant assassin forced to kill by a microchip inserted in her brain, a microchip that also dampens emotions such as love. Carmen needs the code to break the chip’s control over her, and embarks on an audacious plan to get it.

Carmen is a sympathetic character, and the reader is drawn into her attempt for freedom. While too clearly showing its cyberpunk roots and stymied by its predictable ending, "Breaking the Ice" shows that Stephenson is developing as a writer to watch.

Marianne de Pierres’ "Making Contact in Skin-tight Duds", from Eidolon #28, is also a cyberpunk story, but dressed in more technology and streetsmarts than Stephenson’s tale. Loz is a prostitute and killer who, unlike Stephenson’s Carmen, wants to get into an assassination agency (the Zora Assassin’s Alliance), and thinks she has found a way to do it. Organisations, lawful and unlawful, are on the hunt for a man they suspect of being involved in the murder of a famous journalist; Loz thinks he is a stooge, but that he might have valuable ZAA contacts, and she sets out to find him first. But the situation is more complex than anyone knows, and Loz may find herself a ZAA target instead of a ZAA novitiate.

Energetic and clever, de Pierres’ tale nonetheless demonstrates why cyberpunk is beginning to feel old hat. The technology, despite its ingenuity, no longer impresses, and the snappy dialogue, despite its intriguing terminology and slang, subsumes character rather than highlighting it.

In the end, it is character as well as idea that makes a story successful, and yet another cyberpunk tale, Andrew Morris’s "Emotional Bypass", uses character to rise above its mould. While the technology used by journalists and builders in the story is impressive, it is the effect it has on Meri, an ex-broadcast news star, that makes the story zing. Meri is now working on behalf of a community group determined to stop a new road being grown (yes, grown) through its suburb. Quinn, another journalist, arrives at the scene of the protest to do a story on the development. Quinn was sweet on Meri when they were students together, and he is as interested in her as he is in the protest.

"Emotional Bypass" shows that even stale cyberpunk can seem fresh when we care about the characters.

Chris Lawson’s "Chinese Rooms" is a warmly intelligent tale about AI, or rather the idea of AI. Mixing philosophy with science – and using an emotional catalyst to combine the two – Lawson presents us with a question that does not necessarily have any answers. More accurately, there are two answers, but they are mutually exclusive. To cap it off, Lawson adds a postscript to the story that throws the original question open again.

Lawson has a knack of making us care about the effects of the technology he so carefully posits because he convinces us that the effects impact on what it means to be human. Isn’t that what all science fiction should strive to achieve?

Simon Ng’s "The Heart Drummer" hooked me early. I love tales about archaeology. There is something about discovering the past from the clues left behind by our ancestors and their artifacts that satisfies my urge to explore and my need to understand the past (even if only to help explain the present). Ng’s two Australian archaeologists are working on a newly discovered site in China that promises to reveal new and startling facts about that nation’s past, but work on the dig is stopped suddenly by Chines authorities. Reluctant to let go, desperate to reveal the site’s greatest secrets, the pair persist in their exploration and discover a terrible truth …

Stop! If you think this is starting to read like a blurb for a New Age television documentary – combining Von Daniken and "unknown" energies that power the universe – you are right.

Ng’s tale begins well, but ultimately flattens out to a less-than-inspiring conclusion. "The Heart Drummer" is not a bad story, but it could have been so much more.

The same can be said for Jodie Kewley’s "Bare Walls". Kewley is a strong writer, and she creates characters that are easy to care about. Elizabeth is an orphan and overweight. Both factors contribute to her misery and loneliness. In an attempt to overcome some of her problems she attends a rebirthing class. Most of the story is absorbing, and Elizabeth convinces as a real person whose history saddens and bewilders the reader, but the conclusion seems so at odds with the tone and substance of what came before I cannot but think it was tacked on to make it a piece of speculative fiction. "Bare Walls" is a wonderful story cheated by its own ending.

©2000 Simon Brown.

|

SEPTEMBER REVIEWS

Altair #4 |

|

ESSENTIAL READING

Chris Lawson Rick Kennett Helen Sargeant |